During this time of the pandemic, it can be very difficult to stay positive and keep up our spirits. I’m sure the stay-at-home conditions are truly challenging for families, especially for people trying to raise young children and educate them at home or support their online learning. For those of us who live alone, in addition to self-isolating to stay safe, we must find ways of counteracting the boredom, the loneliness, and the possible depression the current situation can cause.

Throughout the world today, political instability, uncertainty, and economic upheavals contribute to the negative situation that so many people are experiencing at this time. There are several different coping strategies we can employ, but for me, one of the best is reading for pleasure.

During the past few weeks, I have been rereading (maybe for the eighth or ninth time) the “Chronicles of Brother Cadfael.” These mysteries are set in England during the twelfth century. Their main character is a Welshman, a former soldier and sailor, who joins a Benedictine monastery in Shrewsbury late in his life. Brother Cadfael is a gardener and an herbalist and – based on his wartime experiences in the Crusades – a doctor of sorts. (Perhaps we can call him a field surgeon.) Cadfael is bilingual in English and Welsh, and often serves as an interpreter when people from the two cultures meet in these stories.

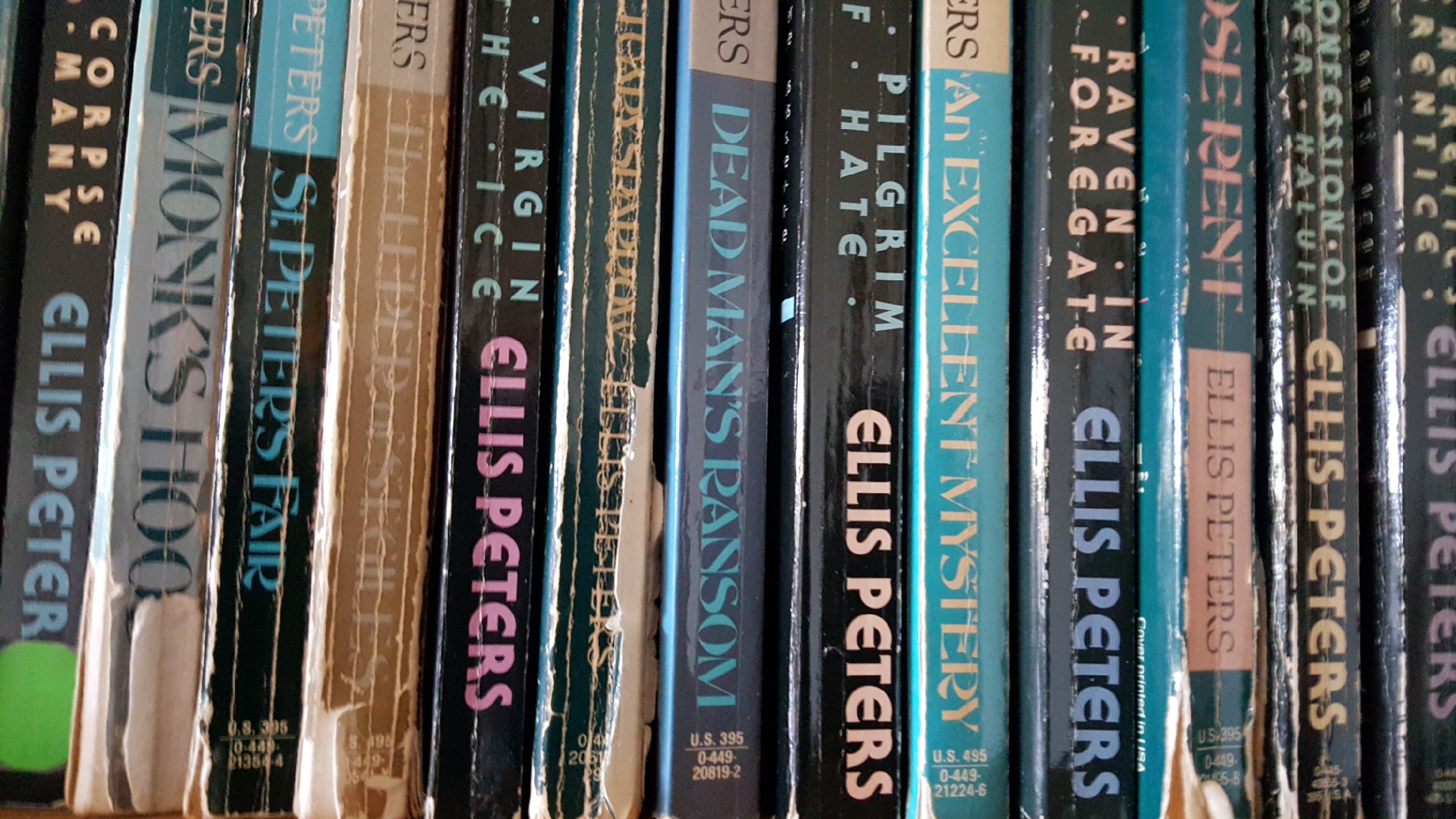

The “Brother Cadfael” novels (and several other books I won’t address here) were written by a British woman named Edith Pargeter (1913-1995), who took “Ellis Peters” as her penname. Her life was seemingly simple but was actually truly amazing, in terms of her accomplishments. For instance, she visited Czechoslovakia in 1947 and then learned Czech (reportedly having taught herself). She subsequently translated many Czech texts and in 1968 she received a prestigious award from the Czechoslovak Society for International Relations. She was also active in civic activities in her home area, where she helped to establish the Shropshire Adult Education College.

Peters had a passion for history and the “Brother Cadfael” stories are set against the backdrop of a prolonged civil war in England, known as the Anarchy, which lasted from 1135 to 1153. The history is fascinating but complicated, and Peters has apparently accurately reported the protracted power struggle between the Empress Maude (the granddaughter of William the Conqueror) and Stephen of Blois (the Empress’ cousin) as the social and economic context for these mysteries.

At the time of the first books in the series, in the year 1138, England is torn by two warring factions, each of which believes in its absolute right to the throne, and each of which includes committed and loyal partisans, ready to give their livelihood, their property, and even their lives in defense of the party they favor. When King Stephen’s forces break the siege of Shrewsbury Castle, they hang all the remaining troops who were loyal to the Empress. As Cadfael tends to the burials with the other monks in the local abbey, he becomes entangled in the chaos when one too many bodies is found among the slaughtered – one who was murdered instead of executed. In uncovering the malefactor, Cadfael first suspects and then exonerates a young nobleman of Stephen’s faction named Hugh Beringar.

Hugh becomes Cadfael’s best friend and literary counterpoint. They are of different generations and different persuasions as to their careers (one a former warrior who has forsworn violence and battle, the other a current officer of the king). Although they begin as antagonists, throughout the twenty-book series they are well matched as friends, colleagues, and allies.

I love these books because they are so beautifully written. They take me out of my own version of 21st-century loneliness, seclusion, and concerns about bickering political factions. To illustrate, in reading this short passage about Cadfael beginning a journey, I imagine myself hiking or riding horseback through the English countryside:

“It was the last of April, a morning all green and silver…. A shower so fine as to be almost imperceptible in the air had followed them over the bridge, where the Severn ran full but peaceful, and before they had assembled in Hugh’s courtyard, the sun had come out fully, sparkling on the leaves and grasses. The river was gilded in every ripple with capricious, scintillating light. A good day to be setting out, and no great matter where or why.” (from The Summer of the Danes, 1991, p. 15)

Thus, one great benefit of pleasure reading is that it can remove us (at least temporarily) from the present, from the trials and tribulations we face, whether we are ill or depressed or locked away and lonely.

But are those distant times and those medieval plots so different from our own circumstances? Consider these repeated themes that emerge in the “Brother Cadfael” stories:

- cultural and ethnic clashes among the Welsh, the English, and the Danes, as well as between the English of Norman and Saxon descent;

- the dominance of a classist society, in which the lives of serfs and free men are controlled by the nobility and royalty – the economic tyranny of the landed gentry over tenant farmers being particularly pervasive;

- the importance of physical boundaries and edifices erected to mark and protect the contested borders between sovereign territories;

- two powerful opposing parties, whose competing claims to the throne divide the country, thereby disrupting trade, manufacturing, and agriculture;

- secret meetings hatching conspiracies among representatives of those parties and splinter groups seeking their own advantage;

- betrayal by political leaders changing their positions and their loyalty, with former allies becoming bitter enemies;

- people incarcerated for their political beliefs or because they had been falsely accused;

- mob violence leading to the unlawful occupation and destruction of property by the rioters;

- invasions of one country by another, or brutal incursions by warring tribes;

- weather extremes and catastrophes that affect the people’s lives and livelihoods, with the welfare of the poor being especially influenced by floods, blizzards, fires, and droughts;

- rape, teen-age pregnancy, and male domination of women, who are seen as property and as access to land and honor through arranged marriages;

- limited healthcare and education, available only to the rich or to those few favored with wealthy patrons;

- fear of contamination from disease, with infected people being ostracized from society;

- disregard for verifiable evidence in favor of the opinions and prejudices of influential people;

- intentional death by poisoning; and

- landowners holding multiple properties while numerous poor people go homeless.

Sadly, these issues are all too familiar in the 21st century. I am sure you can see that several items on this list appeared in the international news of the past year.

Peters introduces all of her characters with memorable descriptions. For example, one powerful land baron is described as entering Cadfael’s awareness (and physical space) in this way:

“Just issuing from the stables and crossing the yard in long, lunging strides, the gait of a confident and choleric man, was someone undoubtedly of consequence in his own domain, richly dressed, elegantly booted, and wearing a sword and dagger. He surged past Cadfael in the gateway, a big burly thrusting man, his face abruptly lit as he swung past the torch fixed at the gate, and then as abruptly darkened. A massive face, fleshy and yet hard, muscled like a wrestler’s arms, handsome in a brutal fashion, the face of a man not in anger at the moment, but always ready to be angry. He was shaven clean, which made the smooth power of his features even more daunting, and the eyes that stared imperiously straight before him looked disproportionately small, though in reality they probably were not, because of the massive flesh in which they were but shallowly set. By the look of him, not a man to cross.” (from The Hermit of Eyton Forest, 1988, pp. 60-61)

This less-than-noble nobleman was a vindictive bully who ultimately met his match and – fortunately – was not seen in any subsequent volumes.

You are probably wondering what any of this book(s) report has to do with TIRF. Well, Brother Cadfael is a researcher – a kind of medieval detective who solves mysteries with the types of data available in his time. (There were no fingerprint records, license plates, DNA testing, or computer searches of databases.) Given his vast knowledge of plants, Cadfael understands the uses – both good and ill – for flowers, leaves, stems, and seeds. In the monastery hut that serves as the abbey’s herbarium, he concocts ointments, painkillers, and remedies for wounds and allergies. His experience as a soldier has also fully acquainted him with death by dagger, arrow, and sword, so he serves as the local pathologist each time a body is discovered.

With Hugh as his collaborator, Cadfael primarily practices naturalistic inquiry, though he does occasionally conduct experiments. He and Hugh observe human behavior, interview people, and review previous findings. They consult other people who have expertise relevant to the particular case. They pose questions and share evidence to test their hypotheses. Between them, Brother Cadfael and Hugh make a formidable team, representing the religious and the secular powers, yet both seeking justice.

The prose of these stories is moving, fresh, and uplifting. Ellis Peters had an amazing vocabulary, with a vast command of beautiful adjectives. Every time I reread these books, I learn new words. (How did I miss them in my earlier readings?) But I suppose the main reason I go back to the “Brother Cadfael” mysteries again and again is that they leave me feeling hopeful. I am now finishing the eighteenth book in the series once more, and I regret that my current exploration of the volumes is coming to another end.

Let me quote again from The Summer of The Danes. Imagine that you and I are riding out with Brother Cadfael as he undertakes a journey fraught with peril:

“On either hand, the trees gathered in moist sunlight after the early morning showers, mixed woodland sufficiently open to let in the radiance of early afternoon, sufficiently close to be ridden in single file, and all just coming into the first full leaf, young and fresh and full of birds. Every spring is the only spring, a perpetual astonishment. It bursts upon a man every year, thought Cadfael, contemplating it with delight in spite of all anxieties, as though it had never happened before ….” (pp. 107-108)

With apologies once more for my Northern Hemisphere orientation (noted in many previous issues of TIRF Today), let me say that as I draft this Chair’s Report, we are experiencing our first serious winter storm on the Central Coast of California. Heavy rain, strong winds, downed trees, power outages, road closures, and flooding have occurred, with mudslides and debris flows predicted. Evacuations have been ordered. Yet the fields beyond my neighborhood are turning green once more, even though it is not yet spring.

Another connection to TIRF is that reading the “Brother Cadfael” stories (like our Foundation) gives me hope, and hope is much needed these days. So, in addition to dealing with the theses, dissertations, textbooks, policy statements, curricula, test reports, and data analyses that are standard fare for language teaching professionals, I hope you are finding time for pleasure reading, and perhaps even for sharing with others information about your favorite books, as I’ve done here.

To conclude, I will cite another of my favorite authors. Mark Twain is credited with having said that history never repeats itself, but it does rhyme. The bulleted list above clearly shows us that the problems of the twelfth century are sadly familiar in the dilemmas we face today. Fortunately, good books – like these tales for our times – endure across the centuries and can bring us hope for the future. Now, as much as ever, we have great need of spring – whether it is literally a season of growth and change, metaphorically a frame of mind, or philosophically a way of life that respects research, teaching, and learning.

Best wishes,